When Hurricane Katrina struck on August 29, 2005, filmmaker Robert Mugge and his son Rob were living in Jackson, Mississippi where Mugge was completing a two-year run as filmmaker in residence for Mississippi Public Broadcasting. The storm’s effects were nowhere near as bad in Jackson as they were along the Gulf Coast, but they were bad enough. After a week without power, Mugge and his son sought to learn what had happened to their musician friends in New Orleans and elsewhere across Louisiana. Gradually, they got word that nearly all were okay, though exiled with their families to other cities throughout the South, often with destroyed houses left behind.

Mugge discussed the situation with his Philadelphia-based associate Diana Zelman, and the two resolved to produce a film on what the storm and breached levees had wrought for the New Orleans music community. He next contacted Starz cable TV executives Stephan Shelanski and Brett Marottoli who had previously underwritten his 2002/2003 film LAST OF THE MISSISSIPPI JUKES and then acquired his 2004/2005 film BLUES DIVAS with Morgan Freeman (produced for Mississippi Public Broadcasting). He explained that he and Zelman wanted to move as quickly as possible to capture the damage and rebuilding efforts in New Orleans itself, while also tracking down and filming prominent musicians in their new, presumably temporary homes elsewhere. Shelanski and Marottoli were intrigued by the idea, yet wary they could pull together the necessary funding on extremely short notice.

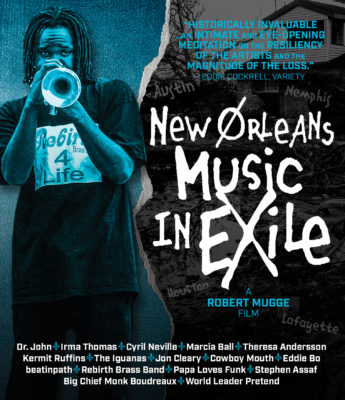

Ultimately, Mugge and Starz worked out a deal where he, Zelman, and a small crew would film the transplanted Voodoo Fest – usually held in New Orleans but, for that year only, mostly moved to Memphis, Tennessee – and the outcome of that effort would determine whether Starz would provide the money needed for them also to shoot in New Orleans and elsewhere. The happy result was successful filming of outdoor performances by Dr. John, Cyril Neville, Cowboy Mouth, Theresa Andersson, beatinpath, and World Leader Pretend; of a recording studio performance by Theresa Andersson intended to open the film; and of a good number of relevant interviews.

In the meantime, Starz assigned new executive Michael Ruggiero to oversee the project, and he was happy enough with reports from Memphis to okay filming in New Orleans as well. Of course, at that point in late October, New Orleans was still barely functioning. For instance, as the film crew quickly learned, most hotels, restaurants, and other businesses were still closed; abandoned cars and boats littered the landscape; the air was dense with particles not conducive to breathing; countless homes were damaged beyond repair; blue protective tarps covered the roof of every second or third building; and stores displayed warnings that looters would be shot. For the most part, people seen on the street tended to be aid workers, construction crews, and Blackwater security guards (unmistakable from their black outfits, automatic weapons, and menacing looks). But somehow, Zelman managed to find rooms in a slightly damaged hotel not far from the French Quarter and figured out which few restaurants were at least partially up and running again.

In New Orleans, the project filmed Papa Loves Funk performing at the Maple Leaf Bar, as well as an intimate home performance by Jon Cleary, recently returned to his darkened Bywater neighborhood and a freezer full of stinking, spoiled meat. Other goals included documenting the overall devastation and recording interviews with key witnesses to what had happened, among them a magazine publisher, a newspaper reporter, a public radio general manager, staff of the charitable Tipitina’s Foundation, and officials of the beleaguered Army Corps of Engineers. Certainly, the most moving shoots involved escorting singer Irma Thomas into her flooded home and nightclub, accompanying label owner Mark Samuels into his equally damaged home and offices, and running into Stephen Assaf at his fully demolished home, barely standing after being washed from its foundation. But perhaps the most unique experience was documenting a local voodoo priestess and her followers as they engaged in a ritual ceremony intended to “bring the dead city back to life again.” Although it’s unlikely this ceremony had anything to do with the city’s ultimate revival, it did, at least in the moment, seem to bring electricity back to the surrounding neighborhood.

The biggest disappointment of the New Orleans visit was the canceling of promised use of an Army Corps of Engineers helicopter to film the closed-off Ninth Ward from above. The problem was that the visiting Prince of Wales wanted a helicopter ride as well, and royalty took precedence. Still, the New Orleans shooting had gone well, so Ruggiero scraped together funding for additional stops in Lafayette, Louisiana, then Houston and Austin. In Lafayette, the crew filmed Marcia Ball and her band in concert at Grant Street Dance hall, where Ball also presented a donated keyboard to her friend Eddie Bo. Bo, who had been playing in Paris when Katrina hit, was currently staying with his manager near Lafayette until he could safely return to New Orleans. The manager was kind enough to invite the entire crew to join her for dinner, after which, they filmed Bo playing a borrowed piano elsewhere in the neighborhood.

Leaving Lafayette, the crew moved on to Houston, where they filmed available members of the ReBirth Brass Band performing in a public park, and then Kermit Ruffins and his band performing at the Red Cat Jazz Cafe. From there, they drove to Austin, where they filmed the Iguanas at the Continental Club and a second performance by Cyril Neville at Threadgill’s.

Buoyed by continuing good news from location, Ruggiero was even able to support a return of the crew to New Orleans. And this time around, thanks to Zelman’s persistence, they finally were given access to an Army Corps of Engineers helicopter for the purpose of filming what was left of the Ninth Ward, the damaged Superdome, and several breached levees, all of which were better viewed from the air. In addition, the crew filmed Eddie Bo again, this time returning to New Orleans and entering his severely damaged coffeehouse for the first time since the storm.

In short, thanks to the timely support from Starz, producer-director-editor Mugge and his crew (producer Diana Zelman, cameramen Dave Sperling and Chris Li, audio person Seth Tallman, and production assistant/photographer Rob Mugge) managed to survey what was happening in New Orleans and several other cities as the catastrophe was still unfolding. As Mugge has said, “While in New Orleans, shortly after Katrina, it was clear we could have pointed our cameras in any direction and found powerful stories to tell. In fact, the devastation was so overwhelming that we were grateful we had decided to focus solely on what happened to the New Orleans music community, because that was a story of manageable scale, yet one which suggested the breadth of the larger human tragedy.”

NEW ORLEANS MUSIC IN EXILE was first shown at the Memphis International Film Festival on March 23, 2006. On May 13, 2006, it was premiered at Canal Place’s Landmark Theatre in New Orleans, followed by a private reception and concert at Tipitina’s French Quarter, where Starz executives presented two $50,000 checks to the Tipitina’s Foundation for their “Instruments A Comin'” and “Hurricane Katrina: Artist Relief” programs. The 114-minute film then premiered on the Starz in Black channel on Saturday, May 19, 2006 and on the main Starz channel a day later.

MVD Entertainment Group is now the worldwide distributor for NEW ORLEANS MUSIC IN EXILE and, as of November 18, 2016, is proud to release it on Blu-ray for the first time. In addition to the film itself, the release includes a wealth of bonus features: public radio executive David Spizale’s illustrated story of rescuing stranded residents from the New Orleans flood waters; Jon Cleary performing a personalized history of New Orleans piano styles; six musical performances not included in the film; and seven extended versions of performances which were included – all of them shot and mastered on HD video.