Christopher Nolan’s Inception is, at its heart, a heist flick and, therefore, adheres to the conventions of one: finding a target, selecting a team, creating the plan and pulling the heist – only something goes awry and improvisation is called for. The only real differences are that a) the idea is not to steal something, but to place something, and b), the scene of the heist [or anti-heist, if you will] is someone’s subconscious – that process is called extraction.

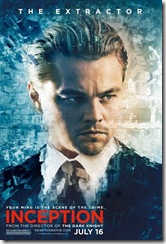

The film opens with a heist in progress – only things don‘t go well and team leader, Dom Cobb [Leonardo DiCaprio] is faced with the choice: face imminent torture and death, or pull of a job that requires him to plant an idea in someone’s mind – this process is called inception, and is widely considered to be impossible. His reward? He will be able to be with his children in the U.S., again [we are told he can’t return to the States, but not why]. The client, Mr. Saito [Ken Watanabe], is the would-be victim of the failed heist.

He accepts the job, so now he has a target. He puts together a team: long time point man and friend, Arthur [Joseph Gordon-Levitt]; Eames [Tom Hardy] is the chameleon who impersonates associates of the victim; Yusef [Dileep Rao] is the man who concocts the specific concoctions that allow the levels of stable slumber required to work in others’ dreams; Ariadne [Ellen Page] is the new architect [the first one has been taken away by Saito’s men] – she constructs the architecture of the dreams in which the team will work. The victim is Robert Fischer [Cillian Murphy], heir to an energy conglomerate of almost indecent proportion. Marion Cotillard, Michael Caine, Pete Postlewaite and Tom Berenger play key roles, as well, but I’ll let you discover them for yourselves.

Whether you enjoy the film depends on whether you buy into Nolan’s conception of dreams and their rules – and whether or not you get lost in the dreams within dreams as the film progresses. Fortunately, Ariadne, being new to this whole process, asks the questions that we might ask – and thinks things through, verbally. Because we’ve come to know Ellen Page for playing characters who are smart and adaptable, her dialogue may veer into areas where, in other movies, it would considered clunky chunks of exposition but it feels right coming from her.

The idea of playing around in one’s dreams isn’t fantasy – many people have “lucid dreams” – dreams in which they’re aware that they are dreaming and can control the events of the dream [full disclosure: I’ve had a number of lucid dreams, myself, so I can vouch for their existence]. From there, it’s not that big a job to accept that we might, possibly, be able to cobble together a technology that would enable us to share dreams – even impose our will on the dreams of others.

One of the problems of shared dreams is the possibility of getting lost in those dreams; losing touch with reality. Nolan has devised a nifty device to allow Dom and his team to avoid this complication – something that is unique to each member of the team.

Then there are the dreams themselves. Nolan explores the rules of dreams – lucid or otherwise – and comes up with feasible explanations for why a dream that might last for a few seconds, or moments, seems to go on for much longer while we’re in the dream, and why we always seem to become aware of dream situations from some point in the middle, rather than the beginning. And then he bends – and sometimes breaks – those rules in unexpected ways [you can’t really break the rules until you know what they are…]. In this way, he presents the grand kink in Dom’s plan – a situation that another team member stumbles onto with unexpected repercussions.

I’m sure that the dreams that we encounter within Inception are filled with symbols that mean something to Nolan – just as some bits will resonant with all viewers –but the symbology of dreams is only one aspect of the film. I’m also certain that, if we took the time to consider them, there are clues to aspects of the film that can be derived from the characters’ names [Ariadne was the daughter of Minos who helped Theseus defeat the minotaur; Robert “Bobby” Fischer was a grandmaster at chess].

Between the events in the film’s real world [a kind of shared waking dream to the audience], and the dreams shared by the film’s characters, we could probably get into spirited discussions of the nature of the conscious and subconscious mind; the likelihood of any new technology being abused for the acquisition of wealth, and even all sorts of questions about ethics – as opposed to morals, not to mention many other related subjects. Or, we could also just let ourselves get lost in what is a joyfully weird execution of that film staple, the heist flick.

Certainly, between the technical aspects of Dom’s plans and the action set pieces set within the fabric of the shared dreams [Arthur’s fight in free fall is particularly noteworthy]; there’s plenty to keep an audience on the edge of its seat. In the sheer scope of the film’s settings, there’s plenty of awe to be generated, but at its heart, Inception is driven by emotion. In the end, that combination is what makes this a film that should be seen.

Final Grade: A+