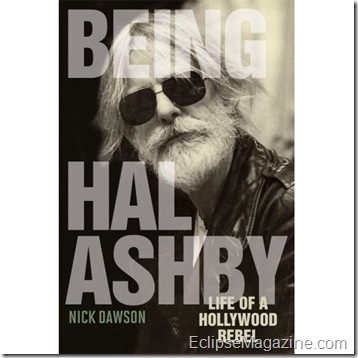

In BEING HAL ASHBY, LIFE OF A HOLLYWOOD REBEL by Nick Dawson (Screen Classics, University Press of Kentucky; 2009), one of the classic American filmmakers is given his due both as an editor and director, in additional to being somewhat of a womanizer, dreamer, addict, and iconoclast.

Dawson gives ample space in the book’s 440 pages to Ashby’s first career as a film editor on such Norman Jewison projects as The Cincinnati Kid (1965), The Russians are Coming, the Russians are Coming (1966), In the Heat of the Night (1967), and The Thomas Crown Affair (1968) before breaking out onto his own as a director. In fact, Ashby was Oscar nominated for editing Russians and Night and won for the latter.

Ashby died before his time at age 59 in 1988, but he left a significant stamp on quirky films of the 1970s. As such, the meat of the book focuses on this highly active and creative period in Ashby’s career. Starting with Harold and Maude (1971), Dawson goes into great detail about the making of these films, and while he did not have first person quotes from Ashby, the author located interviews with the director and his casts and crews, going so far as footnoting and citing all of the quotes in the book.

Certainly, Maude put Ashby the directorial map, and while that film was far from a hit (it disappeared upon its first theatrical release), it became a cult classic, as with many of Ashby’s films of the period. He followed that project with The Last Detail (1973), and became loyal to his crews, such as editor Robert Jones, who cut four consecutive films for Ashby, starting with Detail. Ashby also formed strong friendships with many of his actors such as Jack Nicholson and often shared houses with his many acquaintances.

After Detail, Ashby was no longer an underground figure and was aggressively recruited by Warren Beatty and other producers to direct Shampoo (1975) which vaulted him to the status of a bankable and innovative director, though his hands were tied by Beatty and others on that film. Ashby chose Bound for Glory (1976) as his next film, a starring role for David Carradine, though Ashby was pressured to cast “real” musicians in the role.

Now free to make what he wanted, Ashby was at times attached to projects such as One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Hair, both ironically eventually made by Milos Forman. Instead, he chose the Vietnam protest film Coming Home, as Ashby was not altogether secretly involved in leftist causes in the 1960s and 1970s. Working closely with Jon Voight in an improvisational methodology (though co-star Jane Fonda preferred to memorize all of her lines and work specifically), Ashby carved a momentous piece about veterans of that war, even casting many of them in smaller parts, and was nominated for Best Director for his achievement. His crews also regularly flourished – editor Don Zimmerman from Coming Home is still active and highly sought to this day.

By this point, Ashby was routinely in-demand, being solicited by many actors and studios trying to interest him in their projects. One actor who had loved Harold and Maude and wanted to attach Asbhy to a pet project was Peter Sellers, and the two made Being There together, released in 1979. Alas, with the end of Ashby’s peak decade also came the end of the type of films he was accustomed to making. In their place came big-ticket spectacles and visual effects-oriented films, not Ashby’s forté. As such, his films of that period were hardly the match of the previous decade. However, Ashby would always be noted as a character and actor’s director. In point, 10 different actors received Oscar nominations for performances in his films, with four winning their awards.

In the 1980s, Ashby’s health took a poor turn – his constant drug abuse surely did not reverse this trend. Perhaps that, combined with the different approach of that decade’s films, led to Ashby’s decline in career and person. His last two films, The Slugger’s Wife (1985) and 8 Million Ways to Die (1986) were hardly the stuff of Coming Home and Being There. By the late 1980s, Ashby was suffering from liver and colon cancer and was all but inactive before his tragic death. However, though many of his best films are now 30 years old and onward, his body of work as an editor in the 1960s and director in the 1970s should be examined by today’s artists and cineastes. It is no exaggeration that Ashby is one of the best filmmakers of that period, and Dawson’s amazingly revelatory book is essential reading for all enthusiasts of that era of “rebel” craftspeople in movies.