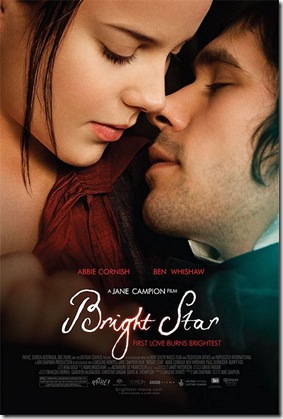

Jane Campion may not have cornered the market on melancholy, but she has definitely shown both a mastery of and a predilection for films that showcase that mood/tone. With Bright Star, however, she infuses the tragic love of Romantic poet John Keats [Ben Whishaw] and Fanny Brawne [Abbie Cornish] with the kind of wit, humor and charm that one expects from a Joe White [Pride & Prejudice].

Keats died at the age of twenty-five, thinking he was a failure, though he is now considered one of – if not the greatest of the Romantic poets. He met Brawne during a fallow period in his writing and, as their mutual attraction grew into love, he regained his creativity. Bright Star is the title of a poem that was, very specifically, about her.

Though Bright Star is of a leisurely pace, it is no mopey, tragedy. Before we are five minutes into the film, Brawne’s young sister, Toots [Edie Martin] and her brother visit a bookseller to pick up a copy of Keats’ Endymion so that Brawne can, in Toots’ words “decide if he’s an idiot or not.” The line, delivered with the kind of breathlessness of a child concentrating very hard to make sure she’s got it exactly right, is only the first instance of the humor that weaves in and out of the first two acts.

There are, of course, those who would confound Keats and Brawne, not the least of these being her mother [who points out that Keats has no money and would, for that reason, not be the best of husbands] and the poet Charles Armitage Brown [Paul Schneider], who seems oddly possessive of him [though not in a sexual sense, as we learn later].

Campion does a very good job of mixing the joy of romantic love with an intelligence and wit that feels appropriate – even necessary. When Keats and Brawne are together, as their love grows, even cramped rooms seem expansive, while the outdoors becomes practically infinite. Once Keats becomes ill, even when she is with him, rooms seem intolerably small and the outdoors shrink to claustrophobic size.

Whishaw and Cornish have amazing chemistry, so it is easy to believe them as lovers – if chaste ones. Both light up the screen as the couple tentatively build their relationship – and virtually explode once they have committed themselves to each other. It is a terrible thing to watch as their love is stymied by Keats’ illness. Love, we see, is not really all we need.

I’m not sure if it was intentional, but the last scene – of Brawne breaking down upon hearing a distraught Brown read an account of Keats’ death – seems curiously detached from the fabric of the film to that point. It strikes the only major false note of the film – which is otherwise quite brilliant.

Final Grade: A-